Johann Georg Hamann:

Language is one of Hamann's most abiding philosophical concerns. From the beginning of his work, Hamann championed the priority which expression and communication, passion and symbol possess over abstraction, analysis and logic in matters of language. Neither logic nor even representation (in Rorty's sense) possesses the rights of the first-born. Representation is secondary and derivative rather than the whole function of language. Symbolism, imagery, metaphor have primacy; “Poetry is the mother-tongue of the human race” (N II, 197). To think that language is essentially a passive system of signs for communicating thoughts is to deal a deathblow to true language.

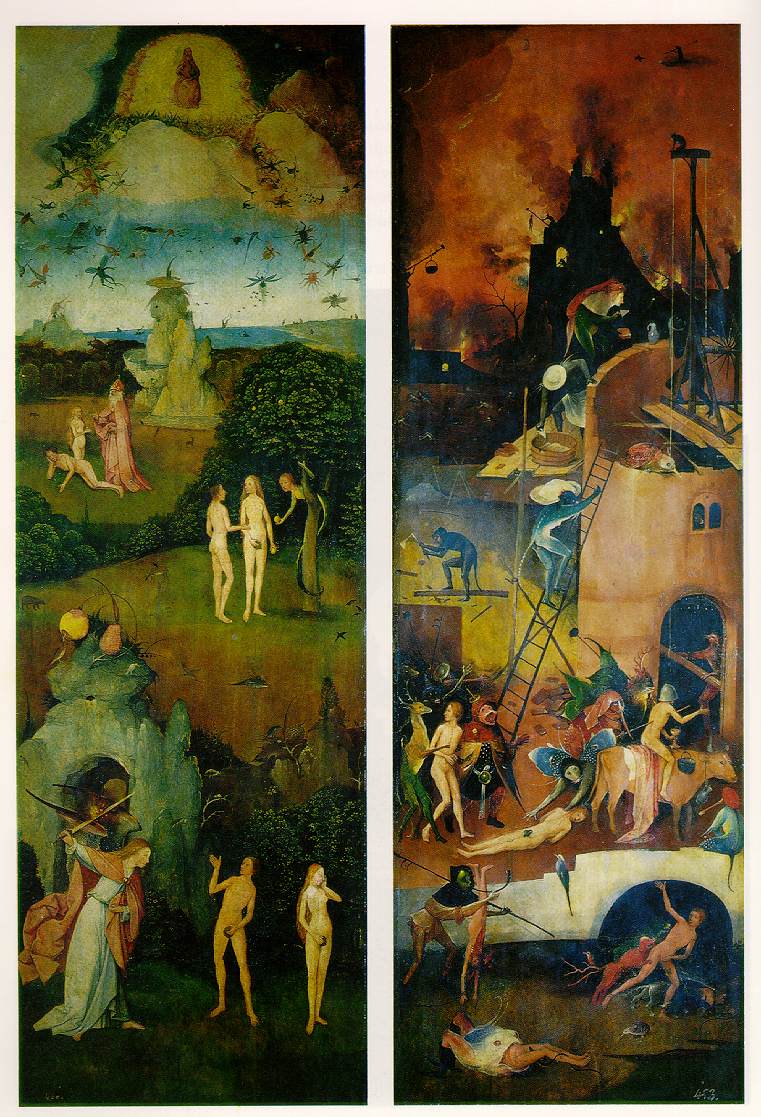

Hamann's answer to a debate of his time, the origin of language — divine or human?—is that its origin is found in the relationship between God and humanity. Typically he has the ‘Knight of the Rose-Cross’ express this in the form of a ‘myth’, rather than attempting to work out such a claim logically and systematically. Rewriting the story of the Garden of Eden, he describes this paradise as:

Every phenomenon of nature was a word,—the sign, symbol and pledge of a new, mysterious, inexpressible but all the more intimate union, participation and community of divine energies and ideas. Everything the human being heard from the beginning, saw with its eyes, looked upon and touched with its hands was a living word; for God was the word. (NIII, 32: 21-30)

This makes the origin of language as easy and natural as child's play.

John Scottus Eriugena discusses the return (epistrophe, reditus, reversio) of all things to God. According to the cosmic cycle Eriugena accepts, drawing heavily on Maximus Confessor and Maximus’ interpretation of Gregory of Nyssa, it is in the nature of things for effects to return to their causes. There is a general return of all things to God. Corporeal things will return to their incorporeal causes, the temporal to the eternal, the finite will be absorbed in the infinite. The human mind will achieve reunification with the divine, and then the corporeal, temporal, material world will become essentially incorporeal, timeless, and intellectual. Human nature will return to its ‘Idea’ or ‘notio’ in the mind of God. According to Eriugena's interpretation of scripture, ‘paradise’ is the scriptural name for this perfect human nature in the mind of God. Humans who refuse to let go of the ‘circumstances’ remain trapped in their own phantasies, and it is to this mental state that the scriptural term ‘hell’ applies.

Articles from Brochure

Philosophy in Paradise—A return to the garden

By Bernice Miller

Dr. Yosef Wosk, Director of the Interdisciplinary Programs at Simon Fraser University at Harbour Center, described the theme as an inquiry into the concept that gardens are places where people can experience innocent, unlimited pleasure; an idea that goes back to the biblical description of the Garden of Eden.

Her notable life's work has been to provide “green living for city dwellers.” Her numerous landscapes in Canada include downtown Vancouver's Courthouse at Robson Square, designed by Arthur Erikson who chose her to do the building's “hanging gardens,” as well as the roof garden of the Vancouver Public Library designed by Moshe Safdi.

Rooftop gardens add to a building's amenities, and also provide energy saving insulation. But is the inclusion or exclusion of garden space in our built environments perhaps also an indicator of our underlying philosophy as to our relationship with nature?

Dr. Wosk asked whether there is a parallel reading to be found between nature and literature. Doesn't the strictly controlled garden develop contiguous with the linear development of literature? And doesn't modern development of innovative movements in modern literature and poetry translate back to affect our perceptions of nature? An even more intriguing question, he noted, is whether we can ever get back to a direct communication with nature.

“ To make a full circle of our meetings,” our moderator Joe Ronsley said at the end of the second Cafe, “let us close with a reading of the scene under rhododendrons, from James Joyce's Ulysses. We agreed, saying “Yes” to the pleasure of these past two days in these dream gardens.

2.1 E. H. Carr's Challenge of Utopian Idealism

In his main work on international relations, The Twenty Years' Crisis, first published in July 1939, Edward Hallett Carr (1892–1982) attacks the idealist position, which he describes as “utopianism.” He characterizes this position as encompassing faith in reason, confidence in progress, a sense of moral rectitude, and a belief in an underlying harmony of interests. According to the idealists, war is an aberration in the course of normal life and the way to prevent it is to educate people for peace, and to build systems of collective security such as the League of Nations or today's United Nations. Carr challenges idealism by questioning its claim to moral universalism and its idea of the harmony of interests. He declares that “morality can only be relative, not universal” (19), and states that the doctrine of the harmony of interests is invoked by privileged groups “to justify and maintain their dominant position” (75).

Carr observes that politicians, for example, often use the language of justice to cloak the particular interests of their own countries, or to create negative images of other people to justify acts of aggression. The existence of such instances of morally discrediting a potential enemy or morally justifying one's own position shows, he argues, that moral ideas are derived from actual policies. Policies are not, as the idealists would have it, based on some universal norms, independent of interests of the parties involved.

“Just as the ruling class in a community prays for domestic peace, which guarantees its own security and predominance, … so international peace becomes a special vested interest of predominant powers” (76).

Carr was a sophisticated thinker. He recognized himself that the logic of “pure realism can offer nothing but a naked struggle for power which makes any kind of international society impossible” (87). Although he demolishes what he calls “the current utopia” of idealism, he at the same time attempts to build “a new utopia,” a realist world order (ibid.). Thus, he acknowledges that human beings need certain fundamental, universally acknowledged norms and values, and contradicts his own argument by which he tries to deny universality to any norms or values. To make further objections, the fact that the language of universal moral values can be misused in politics for the benefit of one party or another, and that such values can only be imperfectly implemented in political institutions, does not mean that such values do not exist. There is a deep yearning in many human beings, both privileged and unprivileged, for peace, order, prosperity, and justice. The legitimacy of idealism consists in the constant attempt to reflect upon and uphold these values. Idealists fail if in their attempt they do not pay enough attention to the reality of power. On the other hand, in the world of pure realism, in which all values are made relative to interests, life turns into nothing more than a power game and is unbearable.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete